The New York Times -- September 17, 1999

ART REVIEW

Egyptian Art: The Mysterious Lure of an Old

Friend

By MICHAEL KIMMELMAN

EW

YORK -- A FEW years ago there was a traveling exhibition,

"Egyptomania," which showed how Greeks and Romans, then Italians,

French, Russians and Americans borrowed, copied and stole from ancient Egypt, or what they believed

was ancient Egypt because after a while the copies and

adaptations got mixed up with originals and became part of the

evolving culture.

EW

YORK -- A FEW years ago there was a traveling exhibition,

"Egyptomania," which showed how Greeks and Romans, then Italians,

French, Russians and Americans borrowed, copied and stole from ancient Egypt, or what they believed

was ancient Egypt because after a while the copies and

adaptations got mixed up with originals and became part of the

evolving culture.

|

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

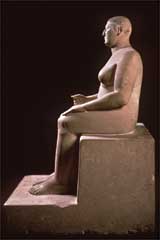

Hemiunu, the prince in charge of

building the Great Pyramid.

|

Obelisks, pyramids and all the other Egyptian-derived forms, which

for centuries, even before the great excavations of the 19th century,

permeated Western art and architecture (the Egyptian Hall in London,

the original Tombs in lower Manhattan, the old suspension bridge over

the Neva in St. Petersburg, the Pyramid at the Louvre in Paris and on

and on) proved that the Egyptians succeeded, to a degree probably even

they didn't anticipate, in leaving a legacy to outlast themselves.

A major show of Old Kingdom art, now at the Metropolitan, easily

gets the early vote for blockbuster of the fall season. Organized at

the museum by Dorothea Arnold and handsomely installed, it's one of

those spectacles, like the Byzantine, Chinese and Mexican surveys that

the Met has done in recent years, that is not just about art but about

a whole civilization. It examines the first great epoch in

Egypt, the 500 years from 2650 to 2150 B.C., which is really

the high point of all ancient Egyptian culture, when the

pyramids were built and the canon of Egyptian art was established. As

well as any show, it demonstrates why Egyptian art still holds an

incredible fascination in the West.

Considering the number and popularity of exhibitions about New

Kingdom pharaohs like Tutankhamen and Amenhotep III, it's a little

surprising that this is actually the first big survey devoted to Old

Kingdom art, but evidently there hasn't been an excuse to do a show

until lately, and museums generally need some excuse for moving around

some of the oldest sculptures in history. The excuse here is that

experts, who for a long time didn't pay much attention to the Old

Kingdom because it seemed like a settled subject, have been fiddling

with the chronology of some of the objects on view. Those of us who

aren't Egyptologists will simply be grateful for the chance to peruse

work that, aside from being astonishingly beautiful, has continued to

seem over thousands of years mysteriously impenetrable and familiar at

the same time.

No doubt this is a reason for Egypt's fascination: its

paradoxical status in our imagination. We think of Egypt as

both complex (hieroglyphs, religion) and, in a formal sense,

rudimentary (the pyramids). Children, for instance, are always drawn,

as if genetically programmed, to the Egyptian section of a museum

because Egyptian art seems immediately understandable to them. To a

child learning to read, hieroglyphs are colorful, eye-catching

pictures, unlike letters of the alphabet, and Egyptian statues, with

their predictable, straightforward attitude toward the viewer, look

like people pared down to basic forms, which is how a child is

inclined to draw.

Adults admire the same art for opposite reasons: it seems abstract

and sophisticated in the sense that we know it depends on a remote

philosophy of nature, religion, authority, class, beauty and death.

Adults always say how Egyptian art looks modern, by which we really

mean that modern art has evolved complicated forms of abstraction,

symbolism and linear representation, many of which ultimately descend

from the Egyptians.

The art is abstract and illusionistic simultaneously. A landmark of

the Old Kingdom from the Fourth Dynasty (2575-2465 B.C.) is the famous

seated statue of Hemiunu, the prince and vizier in charge of building

the Great Pyramid. It's one of the first things that occupies your

attention in the show. Hemiunu is kind of a pyramid himself, a

triangular mass of limestone, life size, straight-backed, feet firmly

planted side by side, hands resting on his lap, one palm down, the

other closed, with a look on his face of divine indifference.

And he's fat -- his large breasts two grapefruits, his huge arms

slack over a frame that, to judge by his head, seems barely sufficient

for his size, his undulating belly sagging under the weight of his

flesh. (You see this best straight on.) A different portrait of him, a

small profile in relief, also in the show, makes him look more

youthful, less forbidding but still fine-featured and strong-jawed, so

that between the two versions we feel we have some idea of what he

actually may have looked like.

This was the essence of Egyptian portraiture: to find a way, within

strict parameters, to convey particularity -- to combine, in a sense,

what one knows with what one sees. Accurate observation was necessary

to fulfill the immortalizing function of Egyptian art -- to be a true

embodiment of the person in stone through eternity -- but observation

always had to be modified by convention.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

Intimate detail: The back of a

sculpture of Iai-ib and Khuaut, husband and wife.

|

You could say that this remark applies to all art, which it does,

but with Egyptian art the limits of convention were unusually

specific. The standard Egyptian relief portrait, as it came to be

established during the Old Kingdom, required each part of the body to

be presented in strict proportion, with its essential aspect to the

viewer (shoulders forward, head turned, legs sideways and striding).

An icon of Egyptian art, anatomically impossible, it's also a

strangely lifelike arrangement.

The artist who carved the relief of Hesi-re, the Third Dynasty

(2649-2575 B.C.) scribe, found a way to obey this formula without

being formulaic and to make us see someone in particular: a tall,

slender young man, serious, with alert eyes, high cheekbones, hooked

nose, narrow mouth, faint mustache and sinewy arms.

We have no idea who the artist was, but while artists didn't carve

their own names into these sculptures, we can tell the good workshops

from the less good ones: the workshop, say, that sculptured the triad

of the Fourth Dynasty king, Menkaure with two goddesses, as opposed to

the one that made the little statues of Inti-Shedu, an artisan --

although they both convey a humane understanding. Some of the most

memorable works aren't the biggest or the fanciest, in fact; they're

sculptures like the one of Iai-ib and Khuaut, husband and wife, side

by side.

She is a little behind him, shorter and standing so close to him

that her right breast presses against his arm. You can make out her

body beneath her sheath dress -- the belly, thighs, hip bones and

back. It's the back that makes the sculpture special: her arm reaches

around him, her hand on his shoulder, an intimate detail that comes as

a particular surprise because it's invisible from the front. We err to

think of Egyptian art as monotonous, even monotonous in a stately,

incantatory way (a common remark). More accurate is to say that it's

an art of subtle variation, especially impressive for operating within

such a strict code.

The Old Kingdom peaked artistically during the Fourth and Fifth

Dynasties (together 2575-2323 B.C.). From the Sixth Dynasty are the

famous statue of Queen Ankh-nes-meryre II with her son, Pepi II, fully

grown in miniature form, sitting on her lap (every mother's dream),

and various standing wood figures of seal bearers, slim, muscular,

vacant-faced, a little toylike but elegant in silhouette. Still, the

essential forms of Egyptian art were in place earlier, when they more

clearly expressed the central Egyptian paradigms of permanence and

immobility.

Egyptian art, after all, was ultimately about death, or more to the

point, it was about eternal life after death, about achieving a

suspended state of grace (another source of Egypt's eternal

fascination for us). What remains of Old Kingdom Egypt are

tombs, or objects from tombs, which represented and recreated the

lives of the people buried. As the textbooks always remind us,

Egyptians made stone sculptures not for the sake of art as we think of

it today but as a duplicate of the living world to be occupied by the

dead, or to be precise about it, by their ka, the life force.

Sculptures of the pharaohs were permanent bodies made of stone to

replace the flesh ones they left behind.

"The Egyptians say that their houses are only temporary lodgings

and their graves are their real houses," is how Diodorus Siculus, the

ancient Greek historian, famously put it (although he might

have added that this sufficed nicely for kings, queens and high

officials with big graves, while for the masses of Egyptians, home for

eternity was a shallow pit).

It's a final, intriguing paradox that an art about death should

teem with so much life. As Ms. Arnold, the curator, writes, "The

essence of Old Kingdom art is joy in life," which is exactly right.

The show is full of paintings, relief scenes and small sculptures of

contented laborers, fishermen, musicians and cooks. Men and women are

always made to look beautiful, even when they're fat or old or dwarfs;

Egyptians depicted everyone with a respect for the diversity of

humanity.

They embraced the ordinary in the afterlife, something that

separates their view of life from our notions of death, which are

fixated on heaven, hell and oblivion. Time after time in the

exhibition, in the way that one experiences small epiphanies by being

alert to what happens all the time on the street, our attention is

drawn to little details from the everyday world: the sexy torso of

Lady Hetep-heres, a statue from the Fourth Dynasty; two orioles

fighting, from a Fifth Dynasty limestone panel; sailors on a ship,

from a relief of the late Fourth Dynasty or early Fifth Dynasty. The

artist who carved that scene demonstrates the Egyptians' mastery of

abstract line drawing, the image being a complicated crisscross of

ropes, oars, legs and masts; even the water under the boat is made

into a kind of braid, jewel-like.

And this is what the best Old Kingdom art is about: conveying the

basic elegance and pleasure of everyday forms in a form that is,

itself, elegant. One relief in the show has a herd of cattle crossing

a canal. The herd is lined up in a strict row except for a cow in

front whose head rears to lick her calf riding on the back of a

herdsman. It's a herdsman's trick for coaxing cows through water: the

mother will follow the calf and the herd will follow her.

The calf here turns around and touches its tongue to its mother's

tongue. An ordinary image becomes something else. The panel was carved

for the tomb of a high Sixth Dynasty official named Ni-ankh-nesut and

is a funerary monument to sweet life.