The New York Times -- December 28, 1999

With New Finds, Egyptology

Flowers

By JOHN NOBLE WILFORD

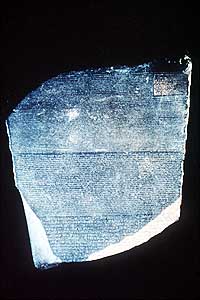

Courtesy The British Museum, London

|

The Indispensable Rosetta

Stone

The object that allowed scientists to decipher

hieroglyphics was discovered 200 years ago. It set the field of

Egyptology in motion, and enthusiasm for the ancient

civilization has yet to subside. |

wo centuries ago,

an engineer with Napoleon's army in Egypt snatched intellectual

triumph from the jaws of military defeat by discovering the Rosetta

Stone. This marked the start of scientific Egyptology, a field that,

more than ever, is bursting with discoveries and new ideas about one

of the most splendid and durable civilizations in the ancient world.

wo centuries ago,

an engineer with Napoleon's army in Egypt snatched intellectual

triumph from the jaws of military defeat by discovering the Rosetta

Stone. This marked the start of scientific Egyptology, a field that,

more than ever, is bursting with discoveries and new ideas about one

of the most splendid and durable civilizations in the ancient world.

Napoleon had landed in the Nile delta the year before, 1798, with

plans to seize Egypt and disrupt the overland link in Britain's vital

trade route to India. "Soldiers, 40 centuries are looking down on

you," Napoleon reminded his troops before leading them to battle

within sight of the pyramids of Giza. His army prevailed over the

Egyptians, but 10 days later, the French fleet was destroyed by Adm.

Horatio Nelson, ending Bonaparte's dream of further conquest.

Of surpassing importance to the scholarship of antiquity, however,

Napoleon brought with him a corps of some 150 scientists, geographers

and linguists from among the best minds of France, an expression of

the Enlightenment in the midst of imperial adventurism. Over several

decades, they described and classified all they learned from the ruins

of ancient Egypt, including the especially rewarding Rosetta Stone.

Inscriptions on the slab of dark basalt found in the summer of 1799

at the site of ancient Rosetta, near Alexandria, were the key to

deciphering hieroglyphics, the formal and ceremonial language of the

pharaohs. Scholars could then read the writings on the walls of tombs

and temples and on the rolls of moldering papyrus. Opened to them for

the first time was more than 3,000 years of the history and religion

behind the monumental ruins along the Nile.

"Two hundred years later, we can read ancient Egyptian almost as

well as any other foreign language," said Dr. James P. Allen, a

curator of Egyptian art and specialist in the culture's language and

religion at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

Perhaps no other branch of archaeology has fascinated the general

public longer and deeper. Tourists flock to the massive pyramids

outside Cairo and the temple ruins of Thebes up the Nile. At museums

people stand in awe before the graceful form of Nefertiti and all the

mummies carefully prepared long ago for the afterlife.

Two major new exhibitions of Egyptian art and artifacts, at the

Metropolitan Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, are drawing

large crowds.

After a thorough cleaning, the Rosetta Stone itself went back on

display last summer at the British Museum. True to the axiom of

warfare that to the victor goes the spoils, the jewel of the French

campaign in Egypt ended up in London.

What is even more remarkable, scholars say, the prodigious

explorations of the last two centuries have only whetted public and

professional appetites, making Egyptology one of the most robust

endeavors of archaeologists. New discoveries have pushed back the

beginnings of Egyptian history. New interpretations of earlier

findings have refined thinking about the lives of pharaohs and their

subjects, the origins and richness of the language and the philosophy

of life and death that inspired the pyramids. Yet mysteries abound,

driving further searches among the ruins.

"It's a growth field," said Dr. Emily Teeter, a curator of

Egyptology at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

"Each year there are probably four or five very significant

discoveries. And there's so much material that has been excavated in

the past but has not been studied."

This year has been

especially rich in discoveries:

• In the desert west of the Nile, between Thebes and Abydos,

archaeologists from Yale found inscriptions that they say are the

earliest known examples of alphabetic writing. Dated to somewhere

between 1900 and 1800 B.C., two or three centuries earlier than

previously recognized examples of uses of an alphabet, the writing is

in a Semitic script with Egyptian influences.

• In the ruins of a 3,700-year-old town near Abydos, excavators

from the University of Pennsylvania uncovered a mayor's mansion. Its

grandeur suggested that at the time mayors enjoyed significant

affluence and political power, in some cases as much as a reigning

pharaoh, and may also have supervised religious activities.

• In the silt of Alexandria harbor, French underwater

archaeologists found numerous fallen stone columns, statues, sphinxes

and masonry blocks with hieroglyphic and Greek inscriptions. Judging

by the location, archaeologists said these could be remains of

Cleopatra's palace in the last century B.C. Her suicide, immortalized

by Shakespeare, was a dramatic stroke in transforming a declining

Egypt into a province of the Roman Empire.

• In another exploration into the Roman period, Egyptian

archaeologists made what they said was one of the most spectacular

discoveries in recent decades. At the Bahariya oasis 230 miles

southwest of Cairo, they found a cemetery of buried tombs extending

over two square miles. In the first four tombs examined, they counted

105 mummies decorated with elaborate masks and waistcoats covered in

gold. As many as 10,000 mummies may yet be uncovered in the place

archaeologists are calling the Valley of the Golden Mummies.

All the while, Dr. Kent R. Weeks of the American University of

Cairo continued exploring the dark interior of the huge tomb for most

of the 52 sons of Ramses II, one of the most powerful pharaohs who

reigned in the 13th century B.C. At the time of its discovery in 1995

in the Valley of the Kings, the tomb was hailed as the greatest royal

find since Howard Carter in 1922 came upon the treasures of

Tutankhamen, the young King Tut.

Dr. Mark Lehner of the University of Chicago kept digging in the

quarters inhabited by workers who built the pyramids at Giza, which

are the last survivors of the so-called seven wonders of the ancient

world. "For those who claim spacemen built the pyramids, we can point

to these workers' villages," Dr. Teeter said.

Dr. Barry Kemp of Cambridge University in England excavated more

sections of Amarna, site of the capital of Akhenaten and Nefertiti in

the 14th century B.C., a revolutionary interlude for Egyptian

sculpture and religion.

At Abydos, 250 miles south of Cairo, Dr. Gunter Dreyer, director of

the German Archaeological Institute in Egypt, continued research that

uncovered evidence of Egyptian kings preceding by two or three

centuries the usual date, 3000 B.C., for the start of the early

dynastic period. A year ago, he reported finding hieroglyphic

inscriptions on pots and bone that were made as early as 3200 B.C.,

possibly 3400. Although controversial, the inscriptions suggested that

writing first appeared in Egypt, not in Mesopotamia, the valley of the

Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in what is now Iraq.

"The scale of individual excavations today is small, compared to

the early expeditions, but the number is larger than ever before,"

said Dr. Rita E. Freed, curator of ancient Egyptian and Near Eastern

art at the Museum of Art in Boston.

"The reason to excavate now is not so much to find beautiful museum

pieces but to answer questions, and they're different questions

compared to those of early generations," she said. "They are more

about the institutions surrounding the temples, and how the people

lived. We know about pharaohs but not a whole lot about what you might

call the man in the street."

The Metropolitan Museum's current exhibition, "Egyptian Art in the

Age of the Pyramids," covers a period of some 500 years, from about

2650 B.C. to 2150 B.C., which ranks as one of the world's most

creative epochs. For reasons still not clearly understood, rulers of

the Old Kingdom, as the period is called, forged a powerful state and

brought people of diverse regions together through a shared national

consciousness. They left a stunning physical legacy in the pyramids,

the enigmatic Sphinx and statues and other works of art that would

define Egyptian culture for centuries to come.

"Egyptians were probably the first to be aware of the nobility

inherent in the human form and to express it in art," Heinrich

Schäfer, a German art historian, wrote in 1919.

Strolling through the gallery at the Metropolitan, Dr. Allen came

to an almost life-size statue of Sepa, a man wearing a kilt and

holding a staff. It is one of the earliest known examples of large

Egyptian nonroyal statuary and evocative of what was happening in this

creative period. "This is Egypt emerging from a two-dimensional

background, all flat and obscure, into something that stands out in

three dimensions," Dr. Allen said.

A significant shift in understanding ancient Egypt began about 50

years ago, Dr. Allen said, with new interpretations of ancient texts

by Henri Frankfort and John Wilson of the University of Chicago. Until

then, scholars tended to see everything with Western eyes, often

concentrating on what Egypt could tell them about the Bible. A deeper

understanding of the nuances of the texts has given scholars a more

Egyptian view of the culture.

In previous translations, for example, the word "ka" was thought to

mean soul or spirit, which has strong Western theological

connotations. Now it is understood, Dr. Allen said, to mean "life

force" or "life energy," the difference between the living and the

dead. Scholars think these and other interpretive changes are giving

them a truer understanding of the Egyptian concept of the afterlife

and the metaphorical writings about creation and the cosmos, a way of

explaining how everything came from a single source that in some way

resembles the Big Bang.

The exhibition at the Boston museum, "Pharaohs of the Sun:

Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen," concentrates on another period of

political change and artistic creativity. In the 14th century B.C.,

the pharaoh who became known as Akhenaten assumed the throne and broke

with past ideologies, notably the religion of many gods. Shrines and

other evidence indicate that most of the people in their homes

continued to worship their several gods, but in official art, the only

god depicted was Aten, and in the temples, the liturgy included "The

Great Hymn to Aten."

Whether Akhenaten was the world's first monotheist is still

debated, Dr. Freed said, but it was clear that he tried to change

Egyptian religion to a belief in one god who was an all-powerful

creator. This god was worshiped through the pharaoh and his chief

wife, Nefertiti, who seemed to share her husband's power. The reforms

of Akhenaten's 17-year reign came to an end during the time of

Tutankhamen, and Egypt returned to most of its old ways.

In the exhibition catalog, Dr. Freed observed, referring to the

seat of Akhenaten's reign, "In many respects, Amarna is still with us

today: in the concept of a single god, man's intimacy with his deity,

naturalistic expression in art, and the ability of a single individual

to dramatically influence the lives of so many."

The many unanswered questions and the expectations of new

discoveries may drive archaeologists, but why the unending popular

fascination with ancient Egypt, ever since the discovery of the

Rosetta Stone?

Perhaps it is the mummies. "Most of us got interested in Egypt at a

young age by being taken to museums to see the mummies," Dr. Freed

said. "Young children discover mummies at the time they are beginning

to comprehend death."

Or perhaps it was the civilization's grandeur and gold, its romance

and intrigue, its imperial ambitions and vaulting hubris. "For a lot

of people," Dr. Allen said, "the big fascination about ancient Egypt

is the amazement of discovering how some of their thought processes

were so very much like those with which we are familiar today."

The grand architecture surely is a factor. Unlike the rival

Sumerians and Assyrians, who had little stone to work with, the

pharaohs commanded the erection of awesome temples and tombs meant to

last the eternity of their anticipated afterlives. The Great Pyramid

of Khufu, which overshadowed Napoleon's troops, rose 482 feet and was

the world's tallest structure until the Eiffel Tower, completed in

1889.

"We as modern people believe in progress, of things getting better

and more sophisticated as time moves forward," Dr. Teeter said. "So

it's with a sense of awe and curiosity that we think about why and how

people in antiquity built such things so long ago without the tools we

have. We wonder if the Egyptians had some knowledge lost to us today."